Historic Adventures-Tales from American History

Tales from American History

Historic Adventures-Tales from American History

Tales from American History

Historic Adventures-Tales from American History

Tales from American History

Historic Adventures-Tales from American History

Tales from American History

Study the chapter for one week.

Over the week:

Activity 1: Narrate the Chapter

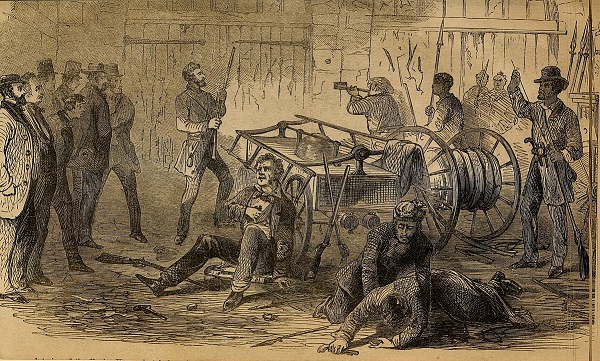

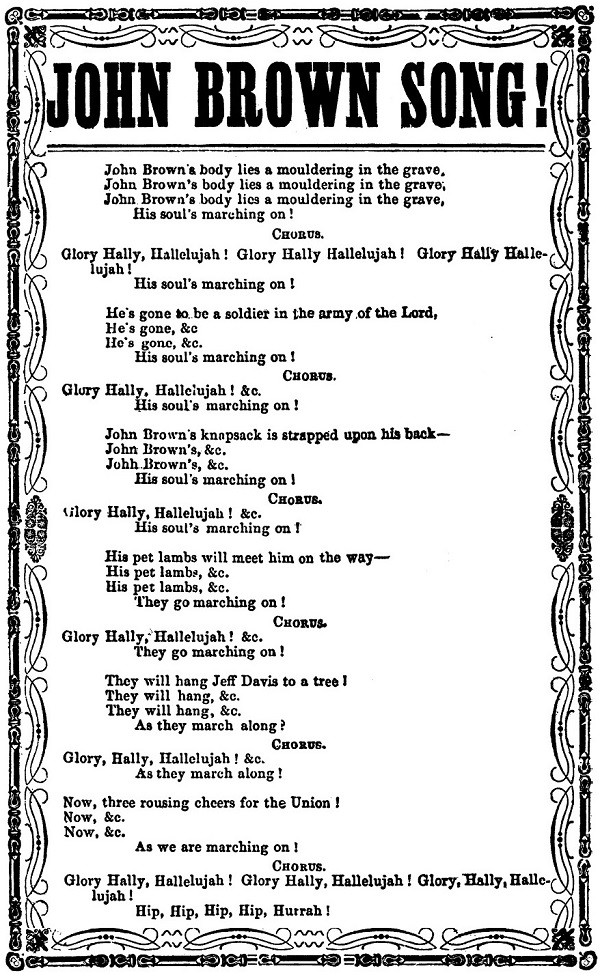

Activity 2: Study the Chapter Picture

Activity 3: Map the Chapter

Find some of the states/regions from the chapter.

Activity 4: Complete Copywork, Narration, Dictation, and Mapwork